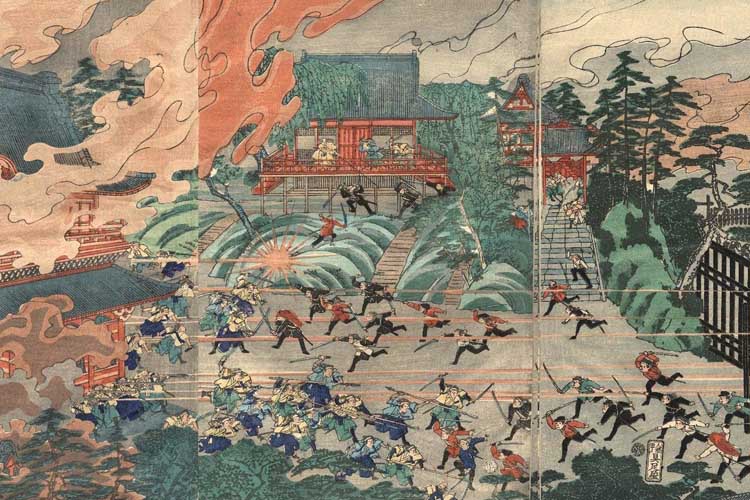

23 October 1868 may well be considered the date marking an immense social transformation for Japan. From this day forth, Japan entered the Meiji era.

Following a period of turmoil that had commenced some fifteen years prior, and the ensuing civil war, the social structure underwent a complete reversal. The system where the shogun stood at the apex and the samurai class governed the nation became a thing of the past.

Throughout the samurai society that lasted for 700 years from the late 12th century, the Emperor remained the nominal sovereign of Japan. However, the Emperor held no real governing power; instead, the shogun, the head of the shogunate in each era, was the de facto ruler.

However, the shogunate system established under the shogun’s authority became increasingly rigid, preoccupied solely with domestic control and stability. It turned a blind eye to foreign relations and exchanges, ultimately failing to keep pace with the changing times.

This was the situation in late-Edo period Japan: concerned by these circumstances, elements of the samurai and intellectual classes rose to save the nation from mounting external pressures and embarked upon fundamental national reforms.

The dawn of the Meiji era. Later, people would call this the “dawn of civilisation and enlightenment”.

Until then, Japan had been a single country, but it resembled a confederation of small states, each with its own feudal lord. Ordinary citizens were in the position of “subjects within these small states”. With the arrival of the new era, the samurai system was completely abolished, and each small state was replaced by a “prefecture” belonging to the Japanese nation.

With the abolition of the samurai system, the existing social hierarchy was relaxed.

Both nobles and commoners were now placed under the Emperor as ‘citizens of the Japanese nation’.

A new political system was established to enrich and strengthen the nation, while simultaneously introducing various goods and cultures from overseas.

Modern architectural techniques, agricultural methods, urban development practices, and entirely new cultures of dress and cuisine – all manner of novelty flooded the streets.

Against such a backdrop, one dish introduced to Japan as “Western home cooking” and which gradually became familiar was the “Croquette”…

However splendid the goods or culture, it is rare for something introduced from overseas for the first time to take root immediately in its original form.

This is because different countries have different climates and customs, and the tastes of their people differ. In most cases, it takes some time for imported new cultures to become familiar. Besides, completely new goods tend to be rather expensive, don’t they? (^_^;)

When croquettes first arrived in Japan, they were initially consumed by the aristocracy and the economically affluent. It was some time before they appeared on the menus of town eateries. Fundamentally, some of the ingredients required were previously unavailable in Japan, so widespread adoption took time. Alternatively, substitutes resembling the original ingredients were used.

As the freedom in people’s lives increased and the economy grew more prosperous, opportunities to taste Western cuisine also multiplied. Consequently, croquettes gradually became incorporated as one of Japan’s home-cooked dishes.

Croquettes are said to have originated in Europe, though each country has its own variations, and their exact country of origin remains unclear. When introduced to Japan, they were reportedly presented as ‘French Korotsuke’.

The name “croquette” first appears in Japanese literature either in the 1887 (Meiji 20) publication “Japanese, Western, and Chinese Cuisine: Their Flavours and Symphony”, or in the 1888 (Meiji 21) work “Simple Methods for Preparing Western Cuisine”.

Croquettes, having become established as a home-cooked dish, were loved by many people and gradually became one of the staples of Japanese cuisine.

Japanese croquettes are fundamentally of two types: the ‘potato-based’ variety, made from mashed potatoes mixed with finely minced meat and onions, and the ‘cream-based’ variety, made from béchamel sauce incorporating crab or seafood.

The oval-shaped, slightly flattened variety is known as the ‘potato base’, while the round, cylindrical variety is called the ‘cream base’.

Adapted to suit Japanese tastes and textures, croquettes have become thoroughly Japanese cuisine over the 130 years since their initial import. Indeed, they are now exported overseas under the name “Korokke”.

In times long past, when Japan shunned overseas trade and withdrew into its own shell, we could not have tasted the diverse cuisines that now surround us as a matter of course.

Dishes arriving from abroad were gradually absorbed into our own cuisine, transformed, and eventually became part of our national culture. Flexible thinking and a passion for refinement made this possible.

When visiting Japan, while savouring ‘pure Japanese cuisine’ (such as sushi or tempura) is certainly worthwhile, do also try dishes imported from abroad and uniquely adapted in Japan. You might find it rather enjoyable to taste the differences compared to the originals enjoyed overseas?

Does your country have any dishes that originated elsewhere and have taken root there…?