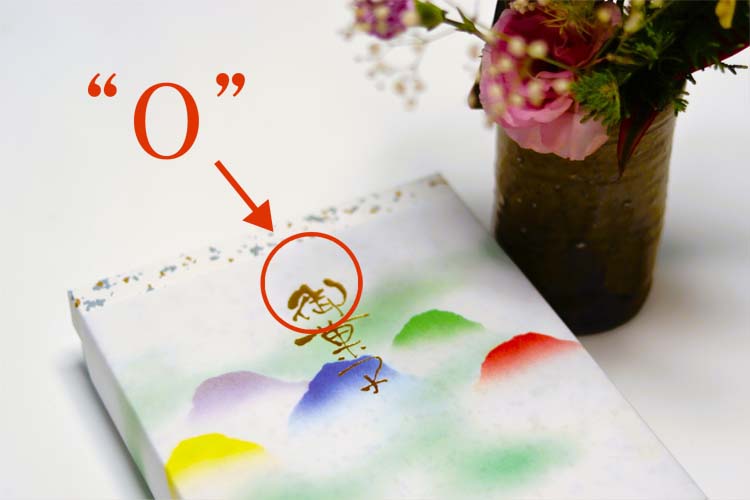

It is pronounced as a short, clipped “O”. It is not pronounced as “oh”.

However, it is sometimes used interchangeably with “Go” or “On”. Although it resembles the English words “go” or “on”, it is unrelated to them and is pronounced just as briefly as “O”.

What might you be referring to?

Prefixes such as “O”, “Go”, and “On” appear quite frequently in Japanese conversation and writing.

Among those who come from overseas with an interest in Japan, it is not uncommon for people to learn some Japanese. However, Japanese is considered a difficult language even on a global scale.

Adding to this, the way these prefixes are applied seems to cause further confusion, troubling those trying to understand Japanese.

“O”, “Go”, and “On” are frequently used phrases, yet the rules governing their usage remain unclear.

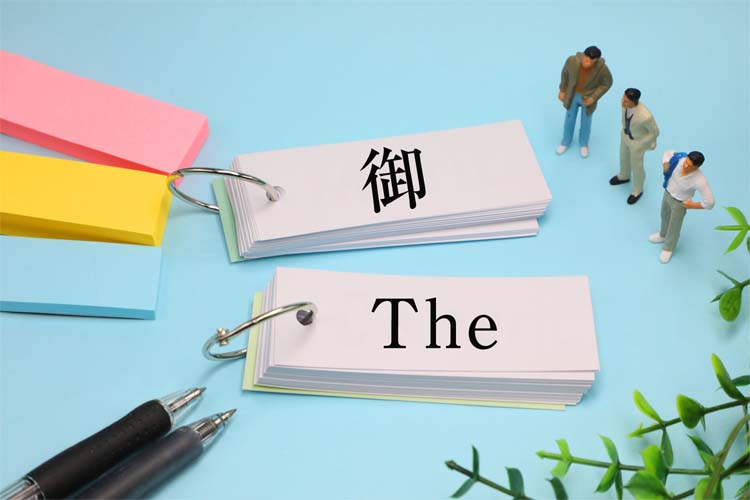

This situation is rather like when we Japanese try to learn and use English, yet find ourselves unsure of the rules for using the definite article “the”.

Why do Japanese people place “O” before words in the first place?

How does this differ from the “the” used in English?

To give the answer upfront, “O” and “the” differ in their purpose of use.

“The” is used in written expression and conversational communication to denote something particularly important or to draw attention to it, and is placed before many nouns. It is a grammatical essential element; omitting “the” can change the meaning of a sentence or spoken phrase.

In contrast, “O” is used to express polite speech or respect towards the listener within the sentence or conversation being conveyed. Its use is not strictly necessary. Sentences can be perfectly formed without “O” or “Go” at all. However, omitting them may be perceived as disrespectful by the listener.

(However, even if people from overseas cannot use the “O” accurately, I believe most Japanese people would find it within acceptable limits. (^^)

In other words, “the” functions like an “arrow” pointing towards various words, whereas “O” acts as a “cushion” that softens the relationship with the person being addressed.

As mentioned several times in previous articles, having lived for thousands of years on an isolated island nation, the Japanese prioritise harmony and smooth functioning within society above all else.

Conversation being fundamental to communication, this linguistic approach is the result of avoiding unnecessary conflict through polite language and a spirit of humility.

Similarly, I hear that many people who come to Japan for work from overseas also find the greetings placed at the beginning of emails exchanged with Japanese people unnecessary.

This too is aimed at fostering smoother relations with others; while not strictly necessary for work, Japanese people feel uneasy without such consideration.

It’s a national trait of the Japanese that foreigners often find rather troublesome. (^_^;)

Now, setting aside the Japanese national character for the moment, let us consider the usage of “O”, “Go”, and “On”.

First, “On” is a rather formal expression. It is used in respectful letters and emails, and while it can appear in conversation, its usage is quite infrequent.

Foreigners learning Japanese need not pay it any particular attention.

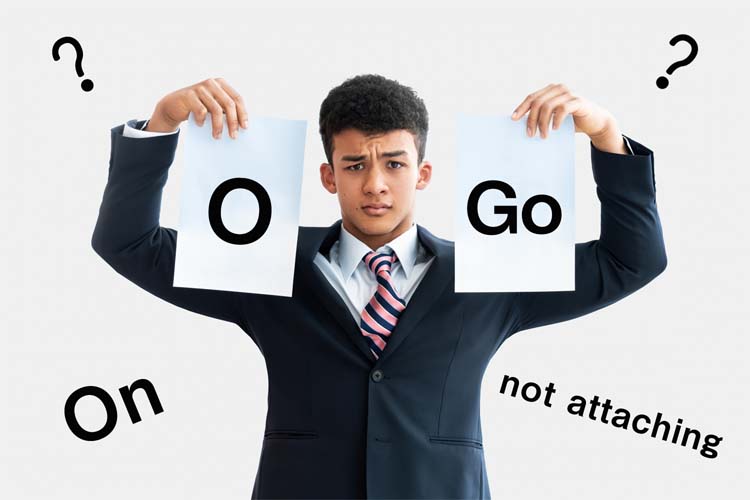

Next, regarding the distinction between “O” and “Go”, this is tricky.

Strictly speaking, there is a rule that “O” is used for kun’yomi readings and “Go” for on’yomi readings. However, those unfamiliar with Japanese or kanji must first learn the difference between kun’yomi and on’yomi, which requires memorising kanji to a certain level.

Indeed, Japanese speakers themselves do not consciously differentiate between them; they use them based on experience and familiarity acquired from childhood.

If I were to venture a suggestion, one might remember that words conveying everyday warmth and softness often take the prefix “O”, while those conveying formal respect and a slightly stiffer tone take “Go”. This rule of thumb should yield about a 60% success rate.

As one example, food and drink items frequently take the “O” prefix.

・O-mizu (water) O-sushi (sushi) O-cha (tea) O-sake (sake) etc.

(Rice is an exception: Go-han)

Words offered to someone within the context of your relationship with them often use “Go”.

・Go-yō (business) Go-annai (guidance) Go-shinpai (concern) Go-kenshō (well-being) etc.

Two final rules not to be forgotten…

As mentioned above, the prefixes “O”, “Go”, and “On” are words used solely to show respect towards others.

No matter how polite you wish to sound, using these words in reference to yourself is incorrect.

Referring to yourself as Go-jibun or your own car as O-kuruma is a misuse…

The other is the ‘rule prohibiting double consonants’.

Japanese people love harmony in sound. If a word already starts with the “O” or “Go” sound, we don’t add another one on top. It would sound like a stutter!

(Example: “Obon” stays “Obon”, not “O-obon”.)

However

Even so…

There are numerous exceptions.

One might even refer to one’s own backside as “O-shiri”.

One might wonder if such polite phrasing is truly necessary even for one’s backside, but indeed, the Japanese frequently employ “O” or “Go” in various words.

O-nabe (hotpot)

O-denwa (I got a phone call)

O-toire (toilet)

O-kazari (decoration / figurehead)

O-bentyara (sycophancy)

Go-taku (tedious talk)

Go-rippuku (annoyance)

This usage softens the impression of the word. While women tend to use it more frequently, men also employ it when necessary.

Did it end up causing more confusion?

I’m sorry I couldn’t offer a more insightful explanation.

Perhaps the only way to truly get used to a country’s language is to live there directly…(^_^;)