Now then, over the past three instalments we have traced the circumstances leading up to the publication of Suzuki Bokushi’s work 「Hokuetsu Seppu」. In this final article, I should like to present several excerpts from its contents, along with another folktale concerning the “Japanese Yeti” that was quoted at the outset of the first instalment.

A text from 180 years ago. The original was written in Japanese, employing archaic language, so here we present a paraphrased version in short sentences.

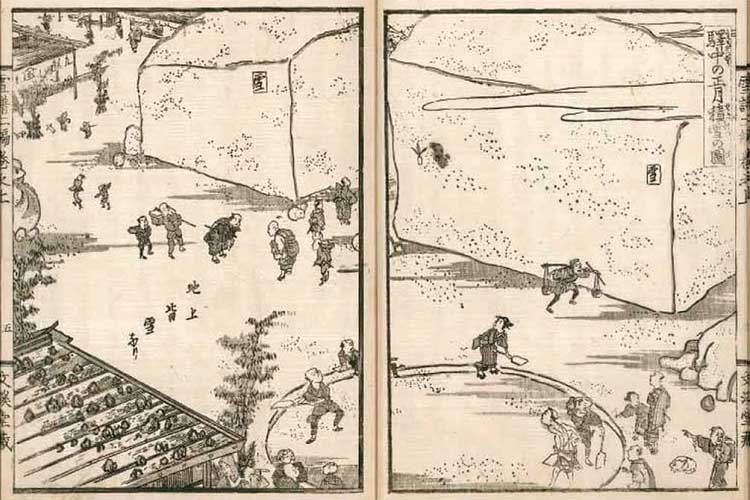

「The depth of the snowfall」

Since ancient times, ten centimetres of snowfall has been described in poetry as “a beautiful sight”, while thirty centimetres causes people to fuss about “a heavy snowfall” – but that is the perception of warmer regions.

In Echigo, three metres of snow is a commonplace occurrence. People are too busy dealing with snow to maintain their livelihoods to have any time for being moved by its “beauty”.

「Snowfall Worthy of Fear」

Though accustomed to life in a snow country, I heard an incredible tale one day. According to an acquaintance living in the neighbouring town, the heavy snowfall near the Chikuma River in 1834 piled up to 55 metres.

It seemed hard to believe at first, but upon reflection, I realised it wasn’t impossible if snowfall of 1.5 metres per day persisted for around three months. Records indicate 1834 was a particularly heavy snowfall year, making it all the more plausible.

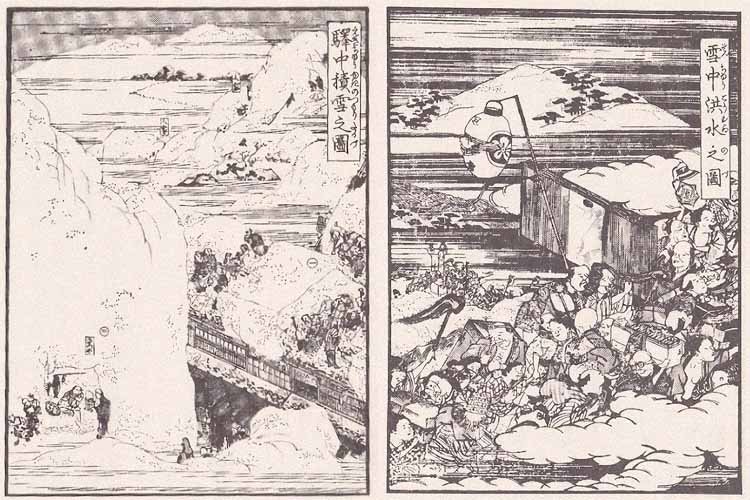

「Flooding Amid Heavy Snowfall」

One day in October, I visited a relative’s house on business and stayed overnight.

In the middle of the night, I was startled awake by sudden commotion within the house. The household members were rushing about, preparing to flee.

Learning that a “snowmelt flood” had occurred, I too became instantly tense.

Snow floods are most likely to occur around the time of the first snowfall and in early spring. Although the village waterways are constantly maintained, heavy snowfall upstream followed by a rise in temperature can cause the waterways to become blocked by snow, leading to overflowing water. This overflowing water, carrying snow and ice, then sweeps through the village.

This time, the damage was minimal and I was spared, but it is not uncommon for such events to become major disasters.

「The Avalanche at the Temple」

In snow country, where snow piles high, one must be wary of avalanches in the mountains. Yet it would be a grave mistake to assume avalanches occur only in the mountains.

Once, the head priest of a temple called Tenshōji was writing. An icicle hanging outside the window obstructed his light, so he stepped outside and struck it with a stick to knock it down.

But the moment he did so, the snow piled upon the roof slid down in an avalanche, sweeping the abbot away.

As the temple stood atop a slope, the avalanche and the abbot slid down the hill for dozens of metres, finally coming to rest where they mounted the embankment. Fortunately, the abbot escaped with only injuries.

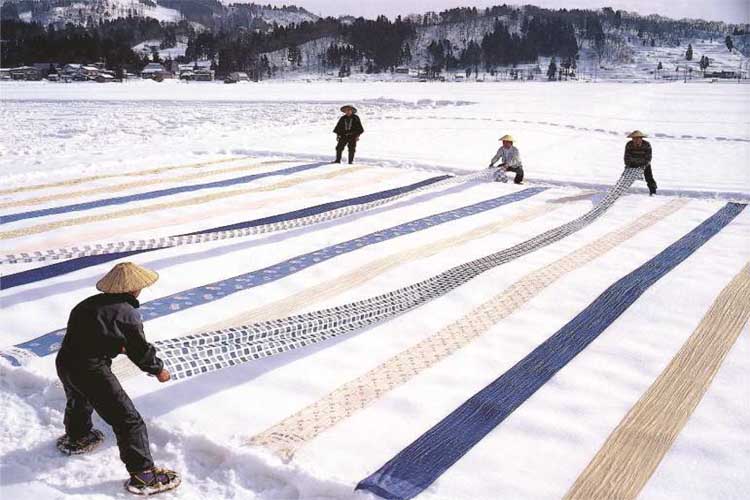

「Chidjimi」

In Echigo, a fabric known as ‘Chidjimi’ is a speciality product.

Chidjimi is a type of woven fabric made from ramie, and is considered one of the finest bolts of cloth.

Echigo became a specialised production area for Chidjimi because it was well-suited to the cultivation of ramie, a type of hemp, and its moderate humidity and cold climate provided ideal conditions for producing strong threads.

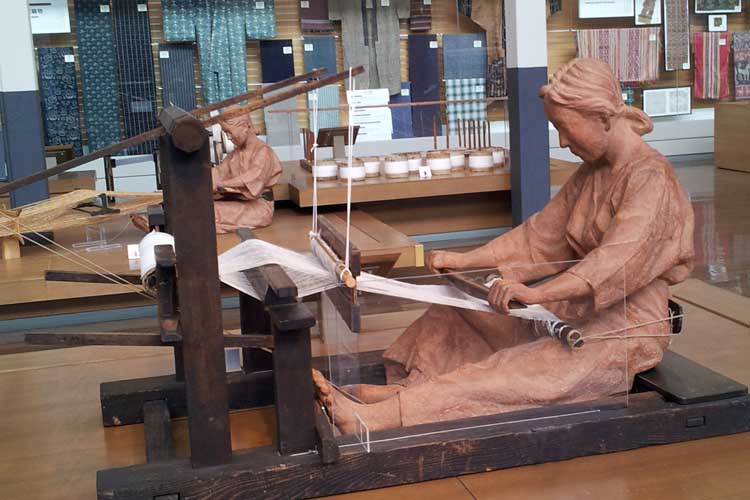

When heavy snowfall limits outdoor activity, weaving Chidjimi becomes the winter occupation for women in Echigo.

Women would purify themselves before commencing work each time. They would straighten their posture and regulate their breathing to spin fine, uniform threads. It was also considered sacred work.

The finished thread is then used on the loom, though the process involves far more steps than ordinary cloth, making it an arduous task. The finished fabric is finished by bleaching it in the snow (to achieve the fabric’s texture and suppleness).

For Echigo, snow is a troublesome adversary, yet it is precisely this climate of snow and bitter cold that makes Chidjimi possible.

「Zaiwatari and Sakabetto」

There is a river called the Shibumi River that flows from Shinano (Nagano Prefecture) through Echigo. In winter, it freezes completely solid, allowing people to walk across it.

Come spring, thick ice breaks into chunks large and small and begins to flow downstream.

As the ice collides and clashes together while flowing, it rushes along with a tremendous roar. This is called Zaiwatari.

Reminiscent of a snowmelt flood, it is not a particularly pleasant sight, so locals seldom go to see it. However, visitors from other regions come to witness this spectacle, gazing upon it while drinking and feasting.

Then, as if to replace these Zaiwatari, Sakabetto appear.

Sakabetto are small butterflies※, and these butterflies fly in swarms along the river, heading upstream from downstream. Their numbers are immense, resembling a cloth flowing through the air.

However, by evening, exhausted butterflies fall onto the river’s surface and drift downstream. Their numbers are again immense. This time, it resembles watching a very long piece of cloth flowing down the river…

※ To be precise, small moths

Within Hokuetsu Seppu, various meteorological phenomena and customs of snow country are introduced in this manner. The episodes covered here represent but a small portion of those contained within.

While some may not seem particularly astonishing by modern standards, to people 180 years ago, these must have been a succession of highly unusual articles. New and fascinating knowledge has a way of captivating people…

Finally, to conclude, I shall present one more tale from the Hokuetsu Seppu concerning the legend of the “Japanese Snowman(Yeti)”, which was also featured in the first instalment of this article.

『The Yeti’s Gratitude』

In a certain village lived a maiden renowned for her skill at weaving.

One day, whilst all the household members were out and the maiden was alone in the weaving room, weaving Chidjimi, a giant of a man appeared at the window, a figure unlike any she had ever seen.

Startled, she tried to flee, but she was unable to escape because she had tied herself to the loom with a cord to keep the warp taut.

The giant showed no sign of violence, merely staring intently at the rice chest in the far corner of the room.

Regaining her composure, the girl untied her waist cord, formed two rice balls, and offered them to the giant. He gratefully devoured them and soon departed for parts unknown.

One day, an urgent order for fine Chidjimi cloth arrived for the daughter from the lord of the land.

The daughter gladly set to weaving, but just then her period began. (In the sensibilities of that time, a woman’s menstruation was considered one form of impurity.)

According to custom, the daughter could no longer enter the weaving room. Unable to weave, she might not meet the deadline for the Chidjimi. She and her parents were overcome with grief…

At that moment, the giant appeared once more before the girl, who was alone.

As she offered him another rice ball, the girl found herself murmuring about their dire straits.

The giant uttered not a word of human speech, but made a gesture as if concentrating on something… then departed…

That very night, the girl’s menstruation abruptly ceased.

Though startled, the girl and her family hurriedly performed purification rites before she entered the weaving room.

She managed to complete the delivery without incident…

This time we presented three stories: the local history “Hokuetsu Seppu” written 180 years ago and the passion of the man who created it, and tales of Japan’s Yeti.

Japan’s Yeti may not be famous, but perhaps due to its approachable nature, it seems to inspire little fear.

Aoki Shuzo, a sake brewery in Niigata Prefecture, is a long-established company with deep ties to Suzuki Bokushi, the author of ‘Hokuetsu Seppu’. They have developed and sell a sake inspired by the Yeti.

Do try it if you get the chance…